This is the thid part of a series of posts about La Verdadera Destreza, the Spanish rapier style, as I practice it. See parts 1 and 2 for some background.

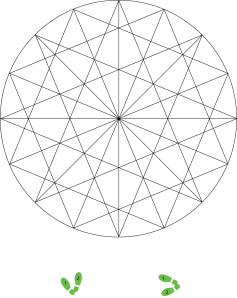

As in any martial art, footwork is of critical importance in Destreza, and even more so since Destreza puts such a priority on positioning. Using the circle, we can precisely codify the various steps, and having done so, we can describe techniques in terms of those steps.

There are eight possible directions of movement: forward/back, left/right, and four diagonals. The left/right steps are called lateral, and the diagonal steps are called transverse (these are historical terms). In all simple (as opposed to passo, which we’ll get to in a moment) stepping, the feet do not cross – that is, the closest foot in the direction of movement moves first. When stepping forward, the front foot moves first; when stepping left, the left foot moves first, and so on.

All steps are done in balance and in control. Destreza has no ballistic movement – that is, there is never a moment when both feet are off the ground, nor when the body weight is projected beyond the base (that is, moving out of balance). Once the diestro begins moving, weight is always on one foot or the other – the only time he is double-weighted is during the transition between feet. For each step, he will dip the post leg (bend his knee) until the free foot can touch the ground (without shifting his weight at all), transfer his weight entirely to the new root, then bring up the trailing foot.

Normally, the trailing foot is not planted. It is left ‘light’, because we expect continuous movement, and the simplest and most natural way to move is to alternate feet (see the description of passo, below). Therefore, usually you’re going to want to immediately step again with the trailing foot.

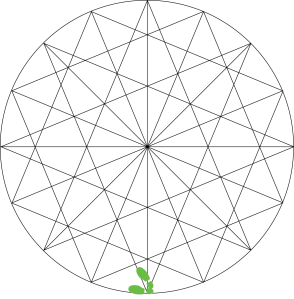

The basic guard position, called afirmarse, looks like this (see part 2 of this series for an explanation of these diagrams):

The forward step takes the diestro to this position; the backward step returns him to his original place:

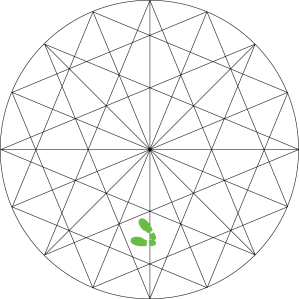

The left and right lateral steps are as follows. Note that they follow the circumference of the circle rather than moving directly to the side:

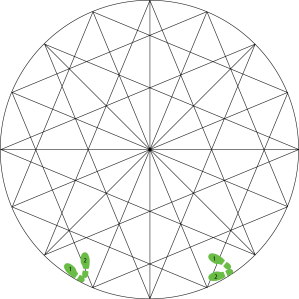

The left and right forward transverse steps are often used to leave the diameter while gaining distance for a counterattack. Note that they turn inwards to address the opponent, rather than maintaining the original orientation towards the top of the diagram:

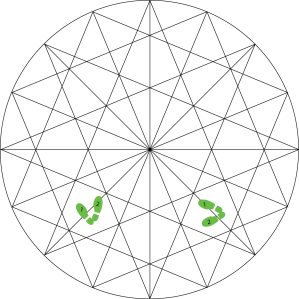

The left and right backward transverse steps leave the circle (but, of course, the circle will follow the diestro – you can’t really leave your own circle, by definition). Note that they also turn inward, just like the forward transverse steps:

Rather than always moving the closest foot, I can move the opposite foot first, crossing my feet in order to step. This is called passo, and it is useful in particular for performing passo naturales – natural stepping, where one foot passes the other. If you take any of the above diagrams and simply reverse the numbers, you will get the passo version of the step. Some of these steps are awkward, such as a forward transverse right passo; that doesn’t mean they’re useless (in particular, one might take that step and then spin to the outside so as to “unwind” the feet), but it does mean that their use should be carefully limited to only specific situations.

So, what’s the point of all this diagramming? What the circle tells us is the area in which action can occur. If I’m at one end of the circle and you’re at the other, I know that I can hit you if I take a single step. I could take a forward step, but I probably don’t want to, because if I walk down the diameter I’m walking onto your sword. So, instead, I’m going to take a transverse step so as to hit you at an angle.

If you attack me, I may take a transverse step (as shown in the example in the previous post) and counterattack; if you attack deeply, say by doing an extended lunge, a transverse step may be too far forward, so I may take a lateral step instead. If you walk the circle, I will initially pace you, using passo naturales. At some point, I may decide to enter the circle in order to attack; again, I will most likely use a transverse step to do this, while you might use a lateral or backward transverse step to evade.

By having all of this drawn out on the ground, you can practice the steps individually until you develop muscle memory. This allows you to fix your range; by knowing that you can take the same transverse step each time, you can memorize precisely how far that step takes you. This, in turn, lets you fix the distance you can reach with an attack, the angle of that attack, the defensive angles you can achieve, etc.

By practicing our footwork until it becomes second nature, we can devote our available brainpower to higher-level concerns such as strategy. In the next part of this series, we will look at the fundamental concepts of bladework; once that’s done, we’ll have all the pieces we need to start assembling some compound motions and examining actual techniques.

3 replies on “Destreza part 3 – Footwork”

[…] Thoughts along the martial Way « Destreza part 3 – Footwork […]

I’ve been looking for some texts on Spanish style footwork. Can you recommend anything?

Unfortunately, there’s damn little available that’s not in Spanish. If you’re looking for historical texts, there’s de la Vega: http://www.thehaca.com/Manuals/destreza.htm#.U4owSJSwI08. There’s also a quasi-translation of Pacheco (aka Narvaez) with links out to the Curtis’ excellent articles: http://www.puckandmary.com/blog_puck/2009/12/pachecos-destreza-curriculum/ and a more-direct translation: http://www.destreza.us/translations/ettenhard.html.

As for modern texts, about the only one I’m aware of is the Curtis’ “From the Page to the Practice”: http://www.freelanceacademypress.com/frompagetopractice.aspx. It’s basically a collection of their articles, so if you read the stuff on their website you can get almost all of it for free.

If you find anything good that’s not in Spanish, I’d appreciate it if you’d let me know!