After several decades of training, I’ve explored quite a few arts. They’ve all got elements in common and they’ve all got differences, but there’s one group that takes a fundamentally different approach and it’s worth looking at them to see what we can learn. The traditional Chinese internal arts are taiji, bagua, and xingyi; they’re often taught together, because they take different approaches that can be complementary.

First, let me describe the three arts and their philosophies, and then I’ll talk about why they’re called “internal” and what that means. I’ll start with a parable that Sensei told me when he was explaining the arts:

Three martial arts masters are traveling up a narrow mountain trail, and meet three other men coming the other way. The taiji master says, “I will yield to you my space, you may pass.” The bagua master says, “I will move around your space and we may both pass.” The xingyi master pauses, looks at the man in front of him, and says, “You’re in my space.”

This parable illustrates the different approaches the different arts take. Taiji is well-known for being a “soft” art – it tries to never oppose force, but rather to always yield to it. In the framework of Musashi’s elements, taiji is water – it never resists, but always sticks to you. Taiji operates both in circles and in lines; its yielding nature means that it always has to adapt to what’s happening around it so it can’t be too opinionated. Its stickiness lends itself well to subtle pushes and pulls that take the opponent off balance, and it includes lots of joint locks and takedowns as well as some striking, though those may not be evident to someone watching a taiji set being performed.

Bagua is known for being circular, but in this context that’s not its most interesting characteristic. Bagua’s circles are used to evade and redirect incoming forces – note “redirect” rather than “yield”. Bagua applies its force at angles in order to manipulate the opponent and the situation; it prefers to evade incoming forces or bounce them away rather than yielding to them. The circular motion lends itself to escapes, joint locks, and throws; they’re on the whole much less subtle than taiji’s approaches, though you still may not be able to see them if you watch a practitioner move.

Xingyi is known for being direct, linear, and comparatively “hard”. It concentrates on strikes that use structure and root to create immense focused power. It uses subtle shifts and angles to facilitate deflecting or simply crashing through incoming forces. This description makes it sound less refined than the other two arts, which is not remotely accurate, but it does look simpler if you see someone practicing it. Bagua’s strikes are obvious – what you can’t see is all the tiny adjustments that make them work.

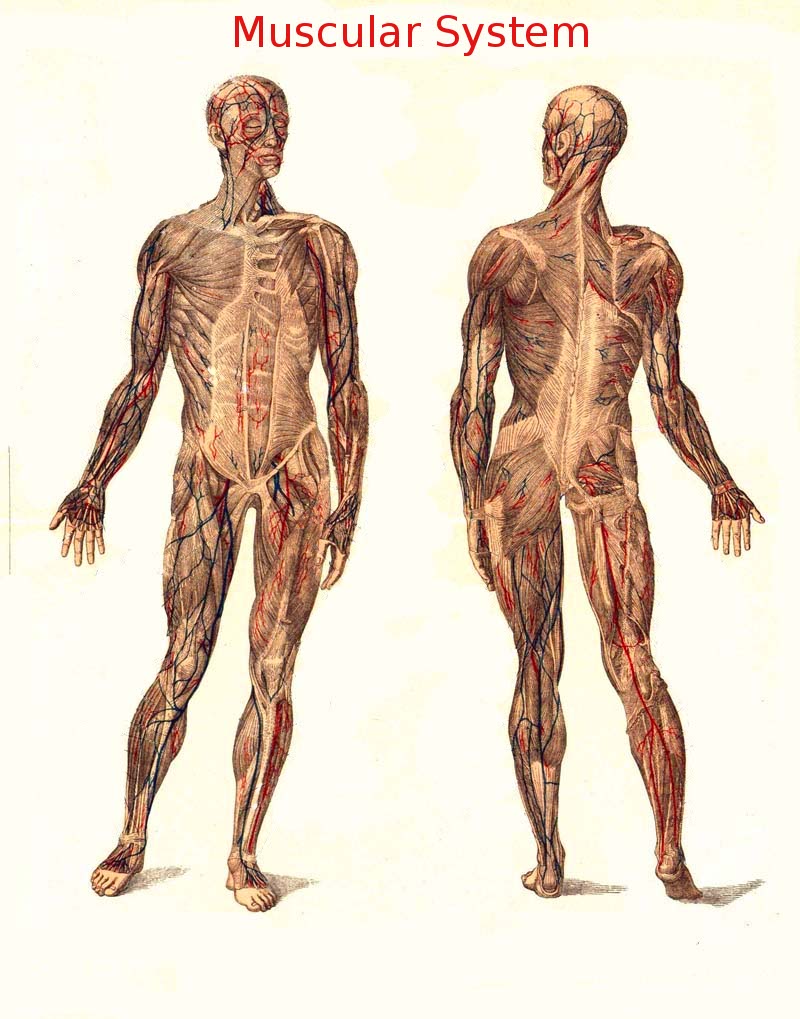

So, what do they all have in common? What makes them “internal” arts? The common aspect of the internal arts is that they focus on taking a relatively small set of techniques and, using excellent body mechanics and approaches, optimizing the hell out of them. Xingyi, for example, has exactly five primary strikes (the “five fists”), and students should expect to spend literally years on each one refining it into its ultimate form.

Without the “excellent body mechanics”, the internal arts are fairly useless for combat – overcomplicated, impractical, and limited. If you take a first-year karate student and put them up against a halfway component opponent, they’ll certainly lose, but they’ll at least look like they’re fighting; if you do the same thing to a first-year taiji student, they won’t have the foggiest idea of what to do, because they’ll have spent all their time perfecting body mechanics and they likely won’t have done any application at all.

There is an often-used metaphor of martial arts as a mountain; this is usually expressed as “different arts are different paths up the mountain, but when you get to the top you end up in the same place.” Compared to the more common “external” arts, internal arts are fundamentally straighter paths up the mountain – they get there in less distance, but the whole path is really steep so your progress may be slow.

In less metaphorical terms, think about your first day of training. If you start practicing, say, kenpo karate, on your first day you’ll be taught a stance or two and probably two or three strikes. The focus will be on getting the gross shape of the movements correct and not on making them really effective – it’s assumed that years of training will be needed before the movements really work. At the end of that day, you’ll be able to punch a bag as if it were an opponent, even though you’d obviously never be effective in a fight.

In your first day of bagua training, you will likely walk in circles. You will be given a great deal of detail on how to walk in circles, but nothing that resembles an application. You’re not only not expected to be able to execute the movements correctly, you’re not expected to even know what to do or why, you’re just expected to do the drills you’re given. You won’t have any idea of how any of this connects to combat or what bagua’s combat applications would even look like.

If you’re training someone to fight and you want them to be effective any time soon, the internal arts are not a great choice. The arts simply aren’t designed to work well in combat for non-experts (this is different from something like aikido, which was never designed to work well in combat at all, even if some experts can make it work anyway).

If your goal is to reach an extremely high level of skill as quickly as possible – understanding that “as quickly as possible” is probably still decades of focused practice – the internal arts are a great choice. The massive foundation required in order to make them work means that when they eventually do work, they work extremely well.

There are also major non-combat applications for the internal arts, and in fact this is the vast majority of their usage today. Taiji, especially, is used for health reasons all over the world. Bagua, with its smooth twisting movements, is also excellent for health; xingyi is less so due to its explosive power, but it’s certainly no worse than any other striking style.

In my opinion, unless you’re really going to go deep on them, internal arts are better positioned as a supplement to other arts. Practicing them has improved my other practice dramatically – it’s given me a far better sense of my body, better structure and root, and a better understanding of how to disrupt other peoples’ structure and root. With all of that, though, I still have no chance of actually applying any of the arts in combat – I just haven’t gone deep enough with them to get all the subtleties that make them really work.

I recommend that every martial artist spend some time with the internal arts if you get a chance. The easiest one is certainly taiji, but finding a martial-focused (as opposed to health-focused) style is challenging, and finding anybody practicing bagua and xingyi is probably unlikely in the US unless you live in a big city. They’re worth seeking out, though – you’ll see big dividends in all of your practice if you invest the effort.